Oslo and Norway hold special places in my heart. For a naive australian young man visiting northern europe for the first time and incredibly susceptible to the romance of the nordic countries.

I was sitting in the cafeteria of the University/School in Oslo, when I glanced upon a copy of SCREAM, a painting so universally known and identified with.

FROM BBC 27 1 2019

Most of art’s iconic masterpieces are renowned for their beauty. Think Leonardo’s smiling Mona Lisa, Vermeer’s luminous Girl with a Pearl Earring and Botticelli’s nude goddess, Venus.

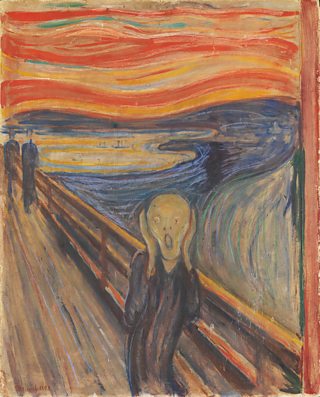

But there’s one glaring exception in the list of all-time greats: Edvard Munch's The Scream. With its pale, hairless figure holding its head in its hands, mouth agape in a tortured howl, it was perhaps an unlikely candidate to become one of the most recognisable and reproduced images of all time.

The Scream, 1893, Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard | Image: National Gallery of Norway

Yet this visceral, doom-laden work – a reflection of the Norwegian artist’s troubled state of mind at the end of the 19th Century – has grown to permeate every aspect of popular culture, from film and TV to memes and tattoos.

You’ll find adaptations and parodies of it on student bedroom walls, on protesters’ placards and in political cartoons. It’s the first painting to have spawned its own emoji – the ‘face screaming in fear’. It has become the ultimate image of existential crisis, the original Nordic Noir.

“One evening I was walking along a path; the city was on one side and the fjord below,” Munch wrote, describing his inspiration for the painting.

“I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord — the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red.

“I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The colour shrieked. This became The Scream.”

An 1895 lithograph print of the work, one of several versions Munch created, is the main draw of a new exhibition, Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, at the British Museum in April. It’s the largest show of Munch’s prints in the UK for 45 years, and will offer a revealing look into his turbulent psyche.

I am not a great fan of Emoji, and very seldom use them, but Scream has its own emoji.

and of course in these days of national anxieties such as the one experienced in USA , cartoons also use the scream as something trapped inside of a person trying to get out, this time at a national level

Munch, struggled with mental illness all his life, having seen members of his family committed to asylum and this depiction of scream of Nature, perhaps so soon after the Krakatoa volcano spilled and coloured the skies, is an inner scream not only of himself but of the humanity , that we are witnessing.

Those visits to Oslo, through rain and snow and sunshine left a deep impression upon me. On my last visit sitting at a cafe from the late 19th century visited by all the intellectuals of that time (Ibsen Larsen Munch among others), one felt a sense of continuity with life. The past is now and the present had been experienced in the past

what would be the emoji when this president leaves office? A modern North American Munch would come up with something relevant..

In the meantime, the British Library is hosting a large collection of Munch's prints and my wish is to be there before it closes.